Item 1, royal names. On NPR’s Morning Edition this morning, people discussing names for the forthcoming British royal baby.

Item 2, unisex names, in particular Taylor.

Item 3, fashions in naming, especially for American Jews.

Royal names. The summary of the Morning Edition story:

The imminent arrival of the future heir to the British throne is spawning gambling, baby products and guessing over names. There’s been no official announcement about when the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge’s baby is due. It’s believed to be Saturday, and the kingdom is prepared.

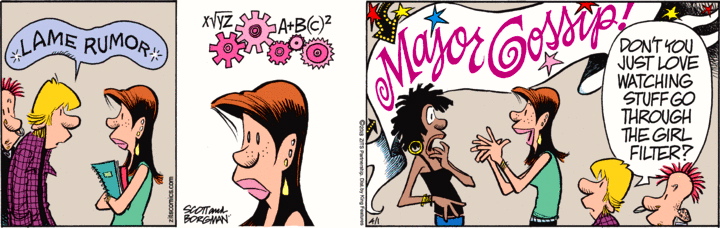

In the discussion, several candidate names were offered; some (Charlotte, Alexandra, Victoria, Elizabeth, Catherine) were judged to be suitably royal names, while others (like Sandra and Sharon) were characterized as non-U or, in the words of one interviewee, “common” — meaning not ‘frequent’ or ‘popular’ (Elizabeth and Catherine are very frequent British personal names, after all), but as NOAD2 puts it, ‘showing a lack of taste and refinement; vulgar’.

Extended discussion in a 7/5 CNN piece, “Queen Ella? King Terry? What’s in a royal name?” by Bryony Jones:

Way back in the mists of time, when schoolkids were expected to learn seemingly endless lists of facts off by heart, they chanted a poem to remember the names of England’s kings and queens.

“Willie, Willie, Harry, Ste,” it began. “Harry, Dick, John, Harry three / One, two, three Neds, Richard two / Harrys four, five, six, then who?” It then ended with the most recent monarchs: “Edward seven, George and Ted / George the sixth, now Liz instead.” [Willie is William, Harry is Henry, Ste is Stephen, Dick is Richard, Ned and Ted are Edward, and Liz is Elizabeth]

Of course, it’s not done that way any more, but if it were, which name would make it into the next verse? We know that “Charles” and “William” will follow “Liz,” but which name will follow theirs?

… Currently sitting at the top of the list for a girl is Alexandra, with bookmakers offering odds of 7/2 or 4/1 in favor of the new baby being named after the wife of King Edward VII, Queen Elizabeth II’s grandmother.

… In recent years, there has been a move away from classic “regal” names by those on lower branches of the royal family tree.

Prince Andrew and his now ex-wife Sarah “Fergie” Ferguson plumped for the unusual Beatrice and Eugenie for Prince William’s cousins. Princess Anne, William’s aunt, has two granddaughters by son Peter and Canadian daughter-in-law Autumn Phillips: Savannah (born in 2010) and Isla (born in 2012).

But [Claudia] Joseph said William and Kate were unlikely to go for more “trendy” options such as Lily, Ella or Ruby, which are a regular feature in annual lists of the most popular baby names. [They are indeed popular, but in the sense of belonging to the people; they are, however, class-marked as non-U, hence not regal.]

“Obviously other members of the royal family have broken with tradition but the offspring of William and Kate will be a future monarch,” she said.

That means, says [Kate] Williams, “we’re not going to see a Chardonnay, or a Plum, or an Apple.” [Or, of course, a Hashtag, which has been suggested.]

Unisex names. The background story: Elizabeth Daingerfield Zwicky and I were chatting aimlessly at breakfast last Saturday when she mentioned that she’d been looking at job applications, including a fair number from Chinese candidates. In most of these cases, their Chinese names gave no clue as to their sex (Elizabeth checked with her Chinese co-workers), but, not to worry, Chinese in the U.S. almost always adopt “English names”, from which sex can be predicted. But in one case, the applicant had chosen the name Taylor. Unfortunately, Taylor is a unisex name.

I cited the (female) singer Taylor Swift, adding that she and (male) actor/model Taylor Lautner had once dated. Elizabeth stared at me in wonderment; how on earth did I (not known to be a follower of Swift’s) come to know such a thing? Well, from Lautner’s Wikipedia page:

In 2009, Lautner was linked romantically to American country pop singer Taylor Swift and American actress and pop singer Selena Gomez.

And why was I reading Lautner’s Wikipedia page? Well, it was research for my “Lycanthropic shirtlessness” posting about him. You pick up all sorts of stuff by accident.

On unisex names, from Wikipedia:

A unisex name (also known as an epicene name or gender-neutral name) is a given name that can be used by a person regardless of the person’s sex. Some countries have laws preventing unisex names, requiring parents to give their children sex-specific names. In other countries unisex names are sometimes avoided for social reasons.

Names may vary their sexual connotation from country to country or language to language. For example, the Italian male name Andrea (derived from Greek Andreas) is understood as a female name in many languages, such as German, Hungarian, Czech, and Spanish. Sometimes parents may choose to name their child in honor of a person of another sex, which – if done widely – can result in the name becoming unisex. For example, Christians, particularly Catholics, may name their sons Marie or Maria in honor of the Virgin Mary or their daughter José in honor of Saint Joseph or Jean in honor of John the Baptist. This religious tradition is more commonly seen in Latin America and Europe than in North America.

Taylor is a family name converted to a personal name; a number of such names have become unisex (usually by starting out as male names). Tyler, for instance, is now occasionally used for women:

His boss was a young woman named Tyler, whom he knew casually in high school. They began dating. (link)

04-10-2012: What better way to celebrate an 0-3 start to the Red Sox season than for the new GM, Ben Cherington, to marry his girlfriend Tyler Tumminia. (link)

Similarly, Ryan:

We know a woman named Ryan but she is 31 years old. Her family just went for it. She’s really nice. I love the name Ryan, but for a boy. (link)

Meanwhile, Jordan, like Taylor, is now pretty frequent as a woman’s name:

Crossing Jordan is an American television crime/drama series that aired on NBC from September 24, 2001 to May 16, 2007. It stars Jill Hennessy as Jordan Cavanaugh, M.D., a crime-solving forensic pathologist employed in the Massachusetts Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. (link)

@Walmart A young woman named Jordan handled the situation perfectly. (link)

And there are other occasional conversions from exclusively male to occasionally female, for instance Justin:

So my name is Justin Danielle Chapman. And I’m a 25 year old mother of two boys, Henry McRae and Beckett Charles. As you can see my name is extremely manly and I want to change it. Since I was a little girl I’ve not liked it. (link)

I was looking for a relaxing massage and he set up an appointment with a nice woman named Justin. My friend was set up with a woman named Devon. (link)

(Devon is a bonus find.)

Fashions in names. Personal names are famously variable from place to place, time to time, and social group to social group; there’s a considerable literature on the subject.

From the deaths in the NYT on the 10th (p. A22), a moving testament to Sidney Joshua Holand and a life that started in Poland, then went through Siberia and Israel and on to the United States. His survivors: daughters Sharon and Adina (both with good Hebrew-derived names), son-in-law Jeff, and five grandchildren:

Evan, Nicole, Zachary, Justin, and Tyler

(Four boys and a girl, though Evan, like Justin and Tyler — see above — is sometimes used as a girl’s name.) Currently fashionable names, only one (Zachary) of Hebrew origin (though it doesn’t connote Yiddishkeit). As for Justin and Tyler: Justin, Jordan, and Jason are all very popular names for young people these days (all three are names of — male — servers at restaurants I frequent, alas), and they are easily confused, as are the popular Tyler and Taylor.

Sometimes the social associations of personal names shift in surprising ways. Some decades ago there was a fashion in the U.S. for Jews to give their sons Celtic names, so that eventually it became likely that a young American man named Sean or Kevin was Jewish.

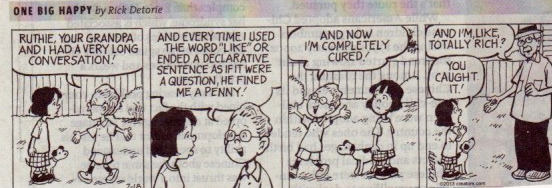

![]()

![]()