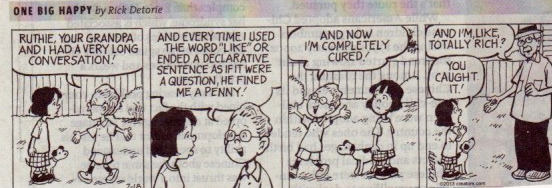

I’ll start with a three-strip series from One Big Happy:

The two features at issue here — the discourse particle like and “uptalk” (a high rising intonation at the end of declaratives) — have been much discussed in the linguistic literature. The popular, but inaccurate, perception is that both are characteristic of young people, especially teenagers, especially girls, and both features are the object of much popular complaint.

(Hat tip to Bonnie and Ed Campbell.)

Then, from Sim Aberson, links to two stories from radio station WLRN in Miami, in a series on the accents of Miami: “Miami Accents: How ‘Miamah’ Turned Into A Different Sort Of Twang” by Gabriella Watts (August 26th) and “Miami Accents: Why Locals Embrace That Heavy “L” Or Not” by Patience Haggin (August 27th). The first of these focuses on features of Spanish that have spread in Miami, after 50 years of waves of Spanish-speaking immigrants to the area. The second focuses on features that contribute to outsiders’ impressions that Miami speech sounds both foreign and feminine — concluding that

In addition to the pronunciation features that pervade their speech, Miamians tend to pepper their sentences with “likes” and end them in “upspeak,” making statements sound like questions. These features can make speakers seem unconfident and overly cute — in short, unprofessional.

(and thus calling for accent-reduction coaching).

The first has a YouTube video with an exaggerated performance of Miami-speak (by a young woman, of course) and then an inventory of “non-native features in Miami English”:

First, vowel pronunciation. In Spanish, there are five vowel sounds. In English, there are eleven. Thus, you have words like “hand,” with the long, nasal “A” sound, pronounced more like hahnd because the long “A” does not exist in Spanish.

While most consonants sound the same in Spanish and English, the Spanish “L” is heavier, with the tongue sticking to the roof of the mouth more so than in English. This Spanish “L” pronunciation is present in Miami English.

The rhythms of the two languages are also different. In Spanish, each syllable is the same length, but in English, the syllables fluctuate in length. This is a difference in milliseconds, but they cause the rhythm of Miami English to sound a bit like the rhythm of Spanish.

Finally, “calques” are phrases directly translated from one language to another where the translation isn’t exactly idiomatic in the other language. For example, instead of saying, “let’s get out of the car,” someone from Miami might say, “let’s get down from the car” because of the Spanish phrase bajar del coche.

Now, on that “heavy L” — a piece of lay terminology that was unfamiliar to me. Spanish /l/ differs in two ways from Standard American English /l/: (1) SAE /l/ is apical alveolar (with the tip of the tongue on the alveolar ridge), while Spanish /l/ is laminal alveolar, often labeled dental (articulated on the alveolar ridge with the blade of the tongue just above the tip); (2) SAE /l/ is velarized in certain contexts (as in both liquids in loll), while Spanish /l/ lacks this velarization in all contexts. (Somewhat confusingly, the tradition in phonetics and phonology is to term velarized /l/ dark and the unvelarized variant light.) From the description above, I gather that “heavy L” is laminal. (On the other hand, /t d n/ are also laminal in Spanish but apical in English, but no one seems to have commented on that feature in Miami.)